The apparent provincialism of the inhabitants of the plains is actually a kind of camouflage:Īlmost anything was possible. In the world of “The Plains,” which both is and isn’t Australia, the plain people and their plain speech also serve to conceal things-elaborate rituals, cosmologies, obscure passions, arcane knowledge. The traces of ancient invertebrates with astonishing names (crinoids, fusulinids, and so on) were just one of many signs that the landscape my coastal relatives used to mock for its monotony in fact harbored wonders. Sometimes, to break up long drives, my dad would pull onto the shoulder of the highway, and we would look for fossils in the limestone that crops out in the road cuts. He captures a plain’s paradoxical mix of uniformity and mystery, the former producing the latter: small differences-a hill, a sudden patch of wildflowers-have an outsized power amid so much sameness they’d fail to stand out among the dramatic natural beauties of California or the overwhelming built spaces of New York. Having grown up in a small capital city located on the Great Plains of North America, I recognize something in Murnane’s descriptions of expansive grasslands, unobstructed sky. His novel “ The Plains,” first published thirty-five years ago and reissued next month, is a bizarre masterpiece that can feel less like something you’ve read than something you’ve dreamed.

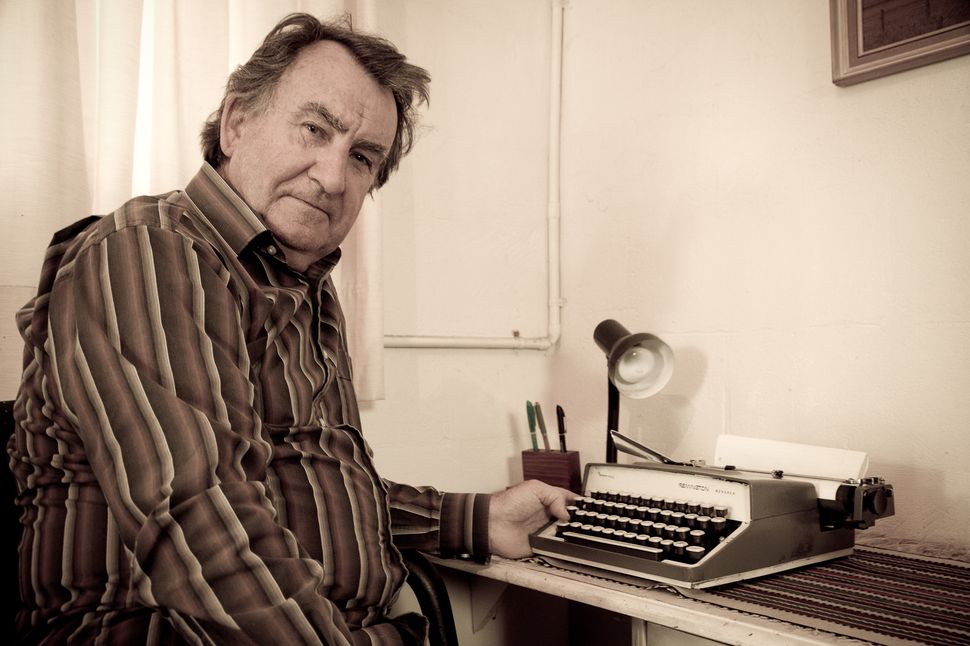

The Australian writer Gerald Murnane was born in a suburb of Melbourne, in 1939, and has spent his entire life in Australia.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)